In my competency work I’ve used ontologies extensively, and for those who don’t know what they are, I’ve decided to make a small simple “101” blog about them.

Ontology stems from a rather old classical philosophical study which deals with the nature and organisation of reality. When I say old I do mean it – I even referenced Aristotle in my PhD thesis, a fact I found incredibly cool!

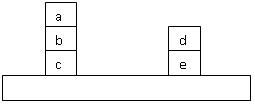

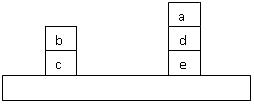

Within computer science, shortly put, it is a logical theory that gives an explicit (partial) account of a conceptualization, i.e. rules and constraints of what exist in a reality. In other words a description of the individual objects in a “world”, their (actual and possible) relationships and the constraints upon them. Take the simple “boxes on a table” world in the picture. The objects would be the table and the boxes = {a, b, c, d, e}. Then several relationships could be made such as table (the boxes that rest on the table, so in this world c and e), on (boxes upon a specific other box, so in this world [a,b], [b,c], [d,e]) and more relationships could be defined. All these relationships are “intentional”, that means they a specifications of what can be not the actual relationships, they can be used to specify other worlds, such as the below world:

Within computer science, shortly put, it is a logical theory that gives an explicit (partial) account of a conceptualization, i.e. rules and constraints of what exist in a reality. In other words a description of the individual objects in a “world”, their (actual and possible) relationships and the constraints upon them. Take the simple “boxes on a table” world in the picture. The objects would be the table and the boxes = {a, b, c, d, e}. Then several relationships could be made such as table (the boxes that rest on the table, so in this world c and e), on (boxes upon a specific other box, so in this world [a,b], [b,c], [d,e]) and more relationships could be defined. All these relationships are “intentional”, that means they a specifications of what can be not the actual relationships, they can be used to specify other worlds, such as the below world:

This gives the opportunity to share the ontologies and use them to describe different worlds and compare them with each other. This is what make them so interesting in computing. There are traditionally 4 different kinds of ontologies: top-level/upper, domain, task and application . (Guarino)

- Top-level ontology (also called upper ontology) should describe high level general concepts, which are independent of domain or specific problems. This would typically be concepts like matter, object, event, time, etc. These should allow for large communities of users, thus enabling tools that work across domains and applications of all the users.

- Domain ontologies and task ontologies should define the vocabularies and intensional relations respectively of generic domains (e.g. medicine, competency or education) and generic tasks and activities (e.g. diagnosis, hiring or reflection). This is achieved by specialising the terms defined in the top-level ontology layer. In practice these two ontology types are often put in a single combined domain and task ontology at this level with one ontology for each domain, as this is easier for the ontology engineer to practically do.

- Application ontologies describe specialised concepts that correspond to roles in the domain performing certain activities. These make use of both the domain and task ontologies.

When developing ontologies for use in real world there are 5 principles that one ought to follow (Gruber):

- Clarity – the formalism of ontological languages ensures this.

- Coherence – there should not be contradictions in the ontology.

- Extendibility – develop with other uses in mind.

- Minimal encoding bias – (an encoding bias results when representation choices are made purely for the convenience of notation or implementation.) This enables several computer systems to speak together.

- Minimal ontological commitment – should only make the assumptions needed for agents to work together leaving the freedom of the agents to create the “worlds” they need internally.

There then exist a large range of different tools that uses these theories to describe the world, and several ontologies that can be used to share knowledge. OWL is probably the most popular ontology language in use, as it is the W3C language for the Semantic Web, it can be used in XML/RDF but there exist many other ways of using it.

A good starting point for using ontologies would be Protégé, which is an ontology editor from Stanford University. There is tons of help on their web site, and the tool really helps the understanding of ontologies, sometimes it just makes sense to see things graphically rather than read it. Having said that I don’t use it anymore, it isn’t even installed on my computer, because it becomes much faster to write ontologies by hand when you’ve understood them.

If you want a more comprehensive “beginners guide” then I personally found this paper by Natalya F. Noy and Deborah L. McGuinness useful when I started down this ontological road.