This post builds on the blog post, so if you haven’t seen it, and do not know about competency representation you probably should! If you don’t know what ontologies are then this post can come to your rescue.

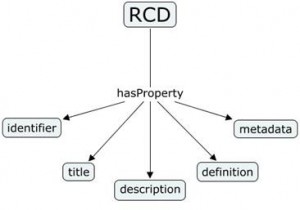

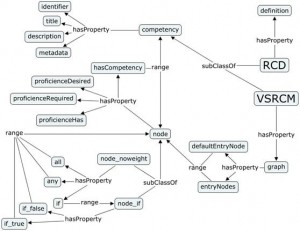

So there is a need to compare competencies. We know how to describe them, and we can even share them between disparate systems, however comparing is really hard, because there is no ontologies describing the different components in the RCD descriptors. We might be able to make some educated guesses in the graph of competencies, but it can only be guesses. If we were to do something more clever we would need to go into natural language processing.

However by specifying ontological relationships between different RCDs it becomes possible to start making comparisons between the different individual RCDs. Unfortunately traditional ontologies relies on formalised relationships which doesn’t really apply to the competency sector, or are too prescriptive. They are also binary in their very nature, i.e. either they exist or they don’t, and the inferences are therefore stringent. This stems from the fact that they are using/based on formalised logics, and as such describe the world using this logic. Fuzzy logic ontologies are being worked on, but that isn’t the biggest problem with ontologies within the competency area – it isn’t that problem of degrees of relationships, but rather degrees of agreements with statements.

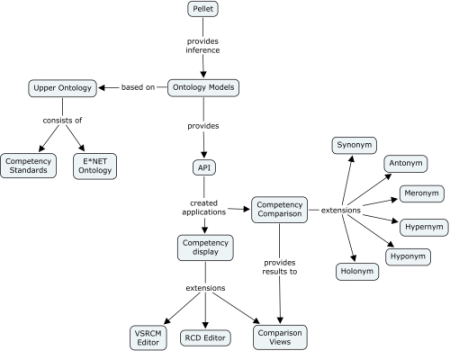

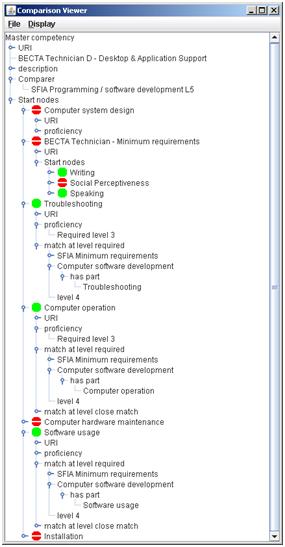

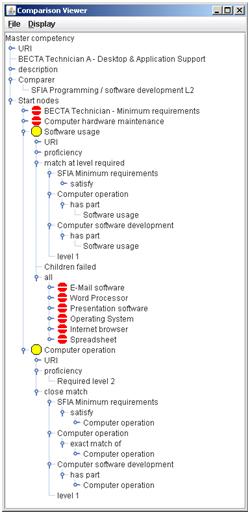

The tool I created was based on standard ontology (OWL) tool set, using OWL and VSRCM graph relationships, based on “traditional” semantic relationships, but I used semantics taken from linguistic theory used in WordNet to describe how different words are related to each othe (e.g. synonyms, antonyms, meronyms, heronyms). In formal ontology this would be regarded as a bad idea, as the resulting semantic inferences would not necessarily be deterministic. To allow for this I developed a system where the results weren’t binary, i.e. true/false or in this case match/non-match, but rather indicated by a “traffic light” matching system if a match was achieved, possible, or not achieved. All of these assessments based on the inferences made within the ontological inferences showing the different inference paths so that the user can assess the validity of the inferences.

This is hardly traditional usage of ontology tools, and truly speaking has proven to be hard to published in traditional ontology literature. A paper describing this has been accepted for Journal of Applied Ontology, but with major changes due to this innovative use of ontology. I’m still struggling with these changes and not sure if I am prepared to make them, or indeed if I can make them and still present my new work. I have also submitted another paper for another journal with a special issue on Competency Management, and we’ll just have to wait and see how it will be received there…

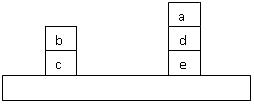

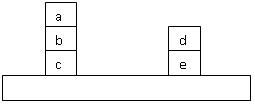

Within computer science, shortly put, it is a logical theory that gives an explicit (partial) account of a conceptualization, i.e. rules and constraints of what exist in a reality. In other words a description of the individual objects in a “world”, their (actual and possible) relationships and the constraints upon them. Take the simple “boxes on a table” world in the picture. The objects would be the table and the boxes = {a, b, c, d, e}. Then several relationships could be made such as table (the boxes that rest on the table, so in this world c and e), on (boxes upon a specific other box, so in this world [a,b], [b,c], [d,e]) and more relationships could be defined. All these relationships are “intentional”, that means they a specifications of what can be not the actual relationships, they can be used to specify other worlds, such as the below world:

Within computer science, shortly put, it is a logical theory that gives an explicit (partial) account of a conceptualization, i.e. rules and constraints of what exist in a reality. In other words a description of the individual objects in a “world”, their (actual and possible) relationships and the constraints upon them. Take the simple “boxes on a table” world in the picture. The objects would be the table and the boxes = {a, b, c, d, e}. Then several relationships could be made such as table (the boxes that rest on the table, so in this world c and e), on (boxes upon a specific other box, so in this world [a,b], [b,c], [d,e]) and more relationships could be defined. All these relationships are “intentional”, that means they a specifications of what can be not the actual relationships, they can be used to specify other worlds, such as the below world: